Understanding Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria: When Red Blood Cells Break Down at Night

Nocturnal hemoglobinuria, also known as paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), is a rare blood disorder in which red blood cells are destroyed prematurely. This breakdown releases hemoglobin into the bloodstream and urine, potentially leading to anemia, fatigue, and serious clotting complications. Because symptoms can be vague or mistaken for other conditions, early recognition is essential for proper diagnosis and long-term management.

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, commonly abbreviated as PNH, represents a complex acquired genetic blood disorder affecting the bone marrow and blood cells. The condition occurs when certain blood cells lack protective surface proteins, making them vulnerable to destruction by the body’s complement system, a component of the immune response. While the name suggests symptoms occur exclusively at night, the breakdown of red blood cells happens continuously, though it may intensify during sleep due to natural changes in blood acidity levels.

The disorder affects approximately one to two individuals per million people annually in the United States, making it exceptionally rare. PNH can develop at any age but most commonly appears in adults during their thirties and forties. The condition results from a mutation in the PIGA gene within bone marrow stem cells, causing the production of defective blood cells that cannot properly defend themselves against normal immune processes.

What is nocturnal hemoglobinuria and how does it affect red blood cells?

Nocturnal hemoglobinuria fundamentally involves the premature destruction of red blood cells, a process called hemolysis. In healthy individuals, red blood cells possess protective proteins on their surface that shield them from the complement system. However, in PNH patients, a genetic mutation prevents the formation of these protective anchors, leaving red blood cells exposed and vulnerable.

When the complement system attacks these unprotected cells, they rupture and release hemoglobin directly into the bloodstream. This hemoglobin then passes through the kidneys and enters the urine, creating the characteristic dark coloration. The destruction occurs continuously but may accelerate during sleep when blood becomes slightly more acidic, explaining why morning urine often appears darkest.

The severity of hemolysis varies considerably among patients. Some experience mild, chronic breakdown with minimal symptoms, while others face severe, life-threatening complications. The bone marrow attempts to compensate by producing more red blood cells, but this response often proves insufficient, leading to persistent anemia and fatigue.

How does dark urine in the morning relate to hemoglobin breakdown?

Dark morning urine serves as one of the most recognizable signs of PNH, though not all patients experience this symptom. The discoloration results from hemoglobin and its breakdown products being filtered through the kidneys during overnight hours. The color can range from tea-colored to cola-brown or even reddish, depending on the concentration of hemoglobin present.

This symptom occurs because hemoglobin released from destroyed red blood cells circulates through the bloodstream until it reaches the kidneys. The kidneys filter this excess hemoglobin, which then accumulates in the bladder overnight. Upon waking, the first urination reveals the concentrated pigmentation that developed during sleep hours.

However, dark urine alone does not confirm PNH, as numerous other conditions can cause similar discoloration, including dehydration, certain medications, liver disease, and other blood disorders. Medical evaluation remains essential for proper diagnosis. Additionally, some PNH patients never develop noticeable urine changes, making this an unreliable sole indicator of the condition.

Why is monitoring anemia symptoms important in PNH?

Anemia represents a central feature of PNH and significantly impacts patient quality of life. As red blood cells continuously break down faster than the body can replace them, hemoglobin levels drop, reducing the blood’s oxygen-carrying capacity. This oxygen deficit triggers various symptoms that can range from mild to debilitating.

Common anemia symptoms in PNH patients include persistent fatigue, weakness, shortness of breath during normal activities, rapid heartbeat, dizziness, pale skin, and difficulty concentrating. These symptoms often develop gradually, causing patients to unknowingly adjust their lifestyle to accommodate declining energy levels. Regular monitoring helps healthcare providers assess disease severity and treatment effectiveness.

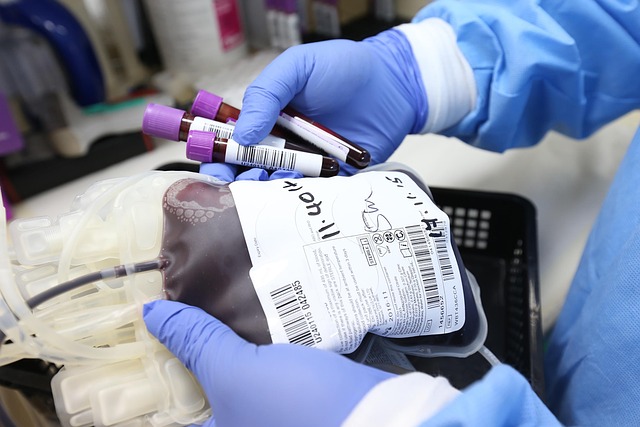

Severe anemia may require blood transfusions to maintain adequate hemoglobin levels and prevent organ damage from oxygen deprivation. Monitoring also helps identify sudden worsening of hemolysis, which may indicate disease progression or the development of complications. Blood tests measuring hemoglobin, reticulocyte count, and lactate dehydrogenase levels provide objective data about the rate of red blood cell destruction and bone marrow response.

How can blood clots signal a serious complication of nocturnal hemoglobinuria?

Blood clot formation, or thrombosis, represents the most dangerous complication of PNH and the leading cause of death among affected patients. Approximately forty percent of PNH patients experience thrombotic events, which can occur in unusual locations including abdominal veins, brain vessels, and other atypical sites. The exact mechanism linking PNH to increased clotting risk remains under investigation, but likely involves the release of clot-promoting substances from destroyed blood cells.

Warning signs of blood clots vary depending on location but may include sudden severe headache, abdominal pain, chest pain, leg swelling, difficulty breathing, or neurological changes. These symptoms require immediate emergency medical attention. Clots in abdominal veins can cause liver damage, intestinal complications, and life-threatening conditions if left untreated.

Patients with PNH often require long-term anticoagulation therapy to reduce thrombosis risk, though this decision must be carefully balanced against bleeding risks. Healthcare providers assess individual risk factors and may recommend preventive blood thinners even before clots develop. Understanding thrombosis warning signs empowers patients to seek prompt treatment, potentially preventing permanent organ damage or death.

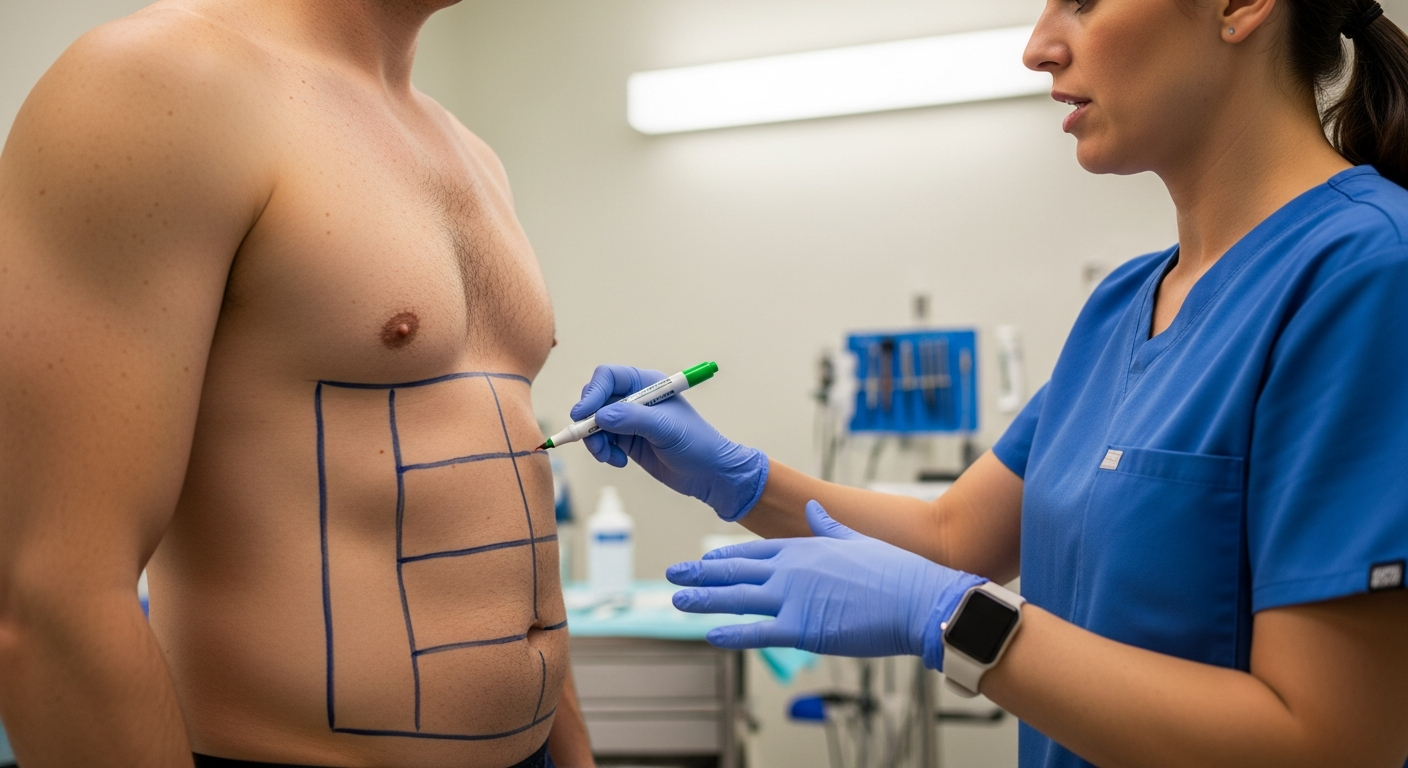

What role do specialized blood tests play in confirming the diagnosis?

Diagnosing PNH requires specialized laboratory tests beyond standard blood work. Flow cytometry represents the gold standard diagnostic tool, identifying the absence of protective surface proteins on blood cells. This test analyzes individual cells using fluorescent markers, determining what percentage of cells lack the crucial protective anchors. A significant population of deficient cells confirms the diagnosis.

Additional blood tests help assess disease severity and complications. Complete blood counts reveal anemia severity and may show decreased white blood cells and platelets. Lactate dehydrogenase levels typically elevate significantly during active hemolysis, serving as a marker of red blood cell destruction. Reticulocyte counts indicate how vigorously the bone marrow attempts to compensate for cell loss.

Historically, the Ham test and sucrose hemolysis test were used for PNH diagnosis, but flow cytometry has largely replaced these older methods due to superior accuracy and specificity. Bone marrow examination may be performed to rule out other blood disorders and assess overall marrow function. Genetic testing can identify the PIGA mutation, though this is not routinely necessary for diagnosis. Regular follow-up testing monitors disease progression and treatment response throughout the patient’s life.

Managing PNH requires ongoing collaboration between patients and hematology specialists. Treatment approaches have evolved significantly in recent years, with targeted therapies now available that can block the complement system’s attack on blood cells. While PNH remains a serious chronic condition, advances in understanding and treatment have substantially improved outcomes and quality of life for many patients. Early recognition of symptoms and prompt medical evaluation remain crucial for optimal management.

This article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Please consult a qualified healthcare professional for personalized guidance and treatment.