Hemoglobinuria: Hidden Body Signals That Point to Serious Issues

Hemoglobinuria can act as a quiet but serious warning from the body, revealing problems that extend far beyond changes in urine color. Often linked to blood cell destruction or kidney strain, its hidden signals are easy to dismiss. Recognizing these signs early may help uncover deeper health issues before they escalate into severe complications.

Hemoglobinuria occurs when red blood cells break apart within blood vessels and release hemoglobin that then passes into urine. Unlike hematuria, where whole red cells appear in urine, hemoglobinuria often produces a clear but reddish to brown color. The change may be most noticeable in the first urine of the day. While dehydration, certain foods, or medications can alter urine color harmlessly, hemoglobin in urine can reflect underlying blood destruction (hemolysis), kidney strain, or both. Understanding the signals can help you recognize when further evaluation is important.

Hidden changes in urine color and what they reveal about internal health

Not every color shift indicates disease, but specific patterns can hint at internal processes. Observing color, clarity, timing (morning vs. daytime), and accompanying symptoms offers clues that distinguish pigment from blood, and blood from free hemoglobin. The following examples describe what various shades can suggest, though lab testing is required to confirm the cause and rule out lookalikes such as food dyes or medications.

- Clear, red to cola-brown urine: can indicate hemoglobinuria or myoglobinuria from muscle injury.

- Cloudy red urine with small clots: more consistent with hematuria (intact red cells) rather than hemoglobinuria.

- Tea or cola color most prominent on waking: consistent with concentrated hemoglobin in urine after nighttime hemolysis.

- Dark brown after strenuous exercise: consider exercise-induced hemoglobinuria or myoglobin from muscle breakdown.

- Orange to amber with strong concentration: may reflect dehydration or bile pigments rather than hemoglobin.

- Pink or red after beets/berries or certain dyes: food-related coloration, not hemoglobin.

- Brown-black with medications (e.g., some antibiotics): drug-related pigment changes.

Early physical signals of hemoglobinuria that are commonly misread or ignored

Subtle body cues can precede or accompany urine color changes. Because they overlap with everyday complaints like dehydration or minor viral illness, people may overlook them. Paying attention to pattern, persistence, and combinations of symptoms can help differentiate transient issues from hemolysis or kidney stress that warrants medical testing.

- Unusual fatigue and paleness that doesn’t match activity level.

- Mild yellowing of the skin or eyes (jaundice), suggesting red cell breakdown.

- Morning headaches with dark first-morning urine.

- Back or flank discomfort unrelated to strain or posture.

- Shortness of breath on exertion, rapid heartbeat, or lightheadedness.

- Brown or rust-colored urine after a fever, infection, or a new medication.

- Leg cramps or cold sensitivity that recur with dark urine episodes.

- Reduced urine output or a sudden strong, unusual urine odor.

How hemoglobinuria reflects underlying blood and kidney dysfunction

Hemoglobinuria usually points to intravascular hemolysis—red blood cells breaking apart within circulation. When this happens, free hemoglobin spills into plasma. Proteins such as haptoglobin bind some of it, but once saturated, excess hemoglobin circulates unbound and can be filtered by the kidneys. In the renal tubules, hemoglobin can stress cells through oxidative effects and iron deposition, sometimes leading to temporary decreases in kidney function. Repeated episodes may cause iron to accumulate in tubular cells, producing hemosiderinuria detectable on specialized testing. In parallel, free hemoglobin scavenges nitric oxide, a molecule that relaxes blood vessels and smooth muscle. Decreased nitric oxide availability can contribute to headaches, abdominal discomfort, or chest tightness in some hemolytic conditions. These mechanisms explain why a color change in urine is not only a urinary finding but also a reflection of broader blood and kidney physiology.

Medical conditions and triggers that can lead to hemoglobin in urine

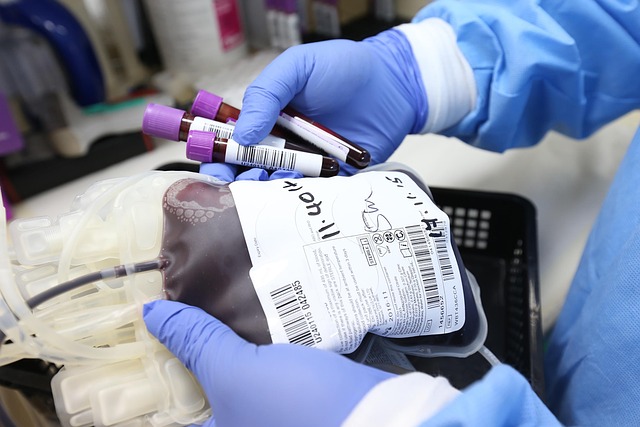

Many processes can cause intravascular hemolysis and thus hemoglobinuria. Some are inherited, some immune-related, and others triggered by exertion, infections, or medications. A careful history—recent illnesses, travel, transfusions, new drugs, or unusual exercise—helps clinicians narrow the causes before confirming with blood and urine tests.

- Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), an acquired bone marrow disorder with complement-mediated hemolysis.

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia, including cold agglutinin disease.

- Transfusion reactions, especially acute hemolytic reactions.

- Infections associated with hemolysis (e.g., certain bacteria) and, less commonly in the U.S., malaria.

- Mechanical destruction from prosthetic heart valves or severe vascular turbulence.

- Exercise-induced hemoglobinuria (long-distance running, marching on hard surfaces).

- Enzyme or hemoglobin disorders (e.g., G6PD deficiency triggers, sickle cell-related hemolysis).

- Toxins or medications that provoke hemolysis in susceptible individuals.

Situations in which hemoglobinuria points to a potentially serious health threat

Most urine color changes are benign, but hemoglobinuria can signal urgent problems. Concern increases when dark or cola-colored urine occurs with severe fatigue, chest pain, shortness of breath, fainting, fever, or flank/abdominal pain. Immediate evaluation is particularly important after a blood transfusion; during an infection accompanied by chills and dark urine; when urine output drops or stops; or if there is confusion, swelling, or new high blood pressure. Recurrent morning dark urine with anemia, abdominal pain, or blood clots suggests a chronic hemolytic process that needs specialist assessment. Distinguishing hemoglobin from myoglobin (from muscle injury) also matters because both can stress the kidneys and may require prompt testing and supportive care.

Conclusion Hemoglobin in urine is a meaningful signal that links the urinary tract to broader blood and kidney function. While foods and dehydration can mimic the color changes, true hemoglobinuria reflects red cell breakdown and deserves thoughtful evaluation—especially when it recurs, appears with other systemic symptoms, or follows transfusion, infection, or heavy exertion. Recognizing these hidden body signals helps frame conversations with clinicians and supports timely testing that clarifies the underlying cause.

This article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Please consult a qualified healthcare professional for personalized guidance and treatment.